Textiles have always been used extensively in Buddhist temples for both decorative and practical purposes. Many of the fabrics thus used were donated to the temple by the lay community.

In Buddhism, the act of giving is considered one of a number of pious deeds that allow a person to accumulate spiritual merit during his lifetime and which may benefit him along the path to liberation. The practice of donating textiles to temples was carried out by members of all levels of society, no one being considered too humble, though the most lavish gifts were made by emperors and shoguns.

With their rich polychrome designs, enhanced by large quantities of gold or silver thread, they represent the most complex and luxurious forms of weaving of the period. As its name indicates, the altar cloth, or uchishiki in Japanese, serves to cover the top surface of certain altars and tables in Buddhist halls, most frequently those placed in front of the main image or images, as well as smaller side tables.

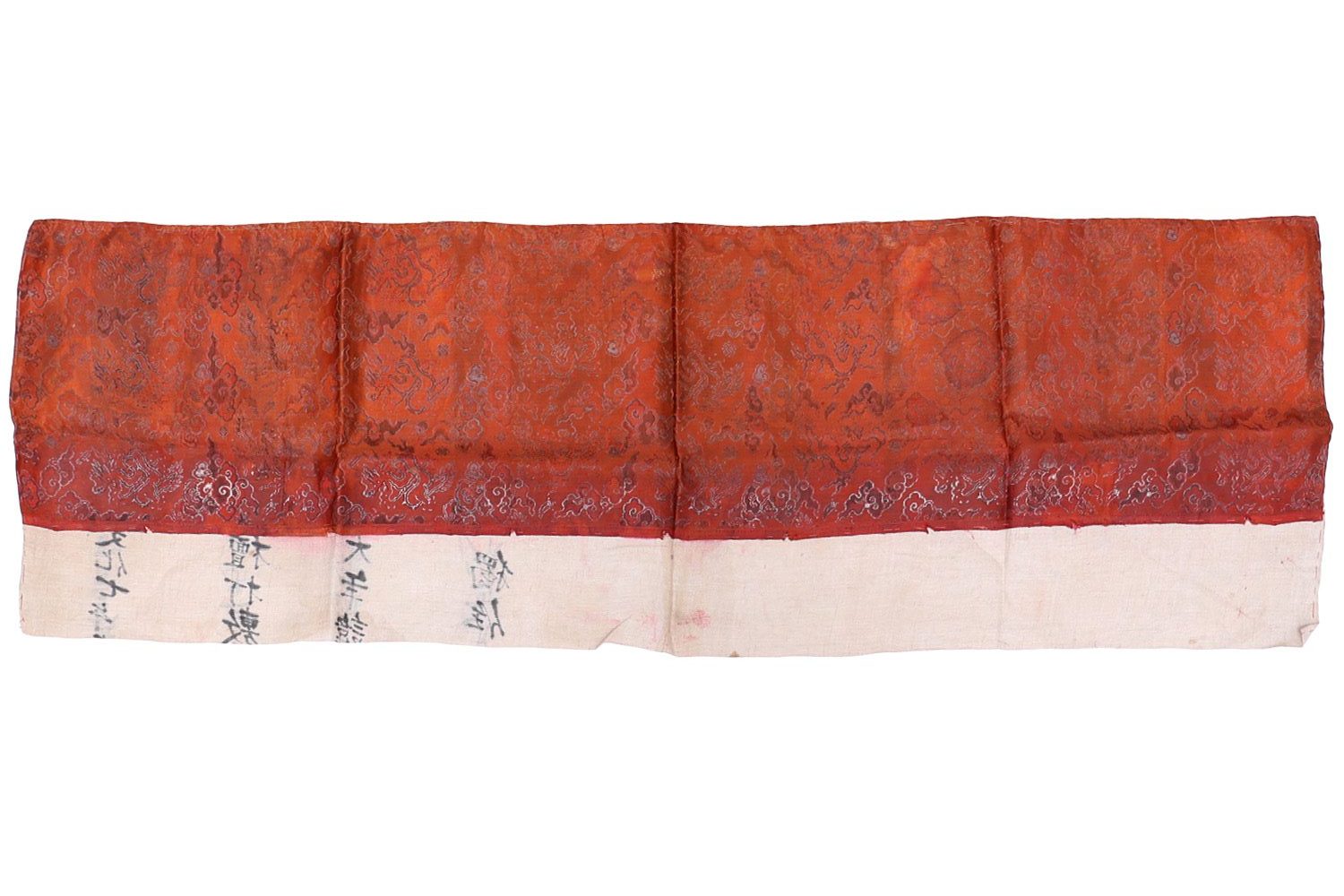

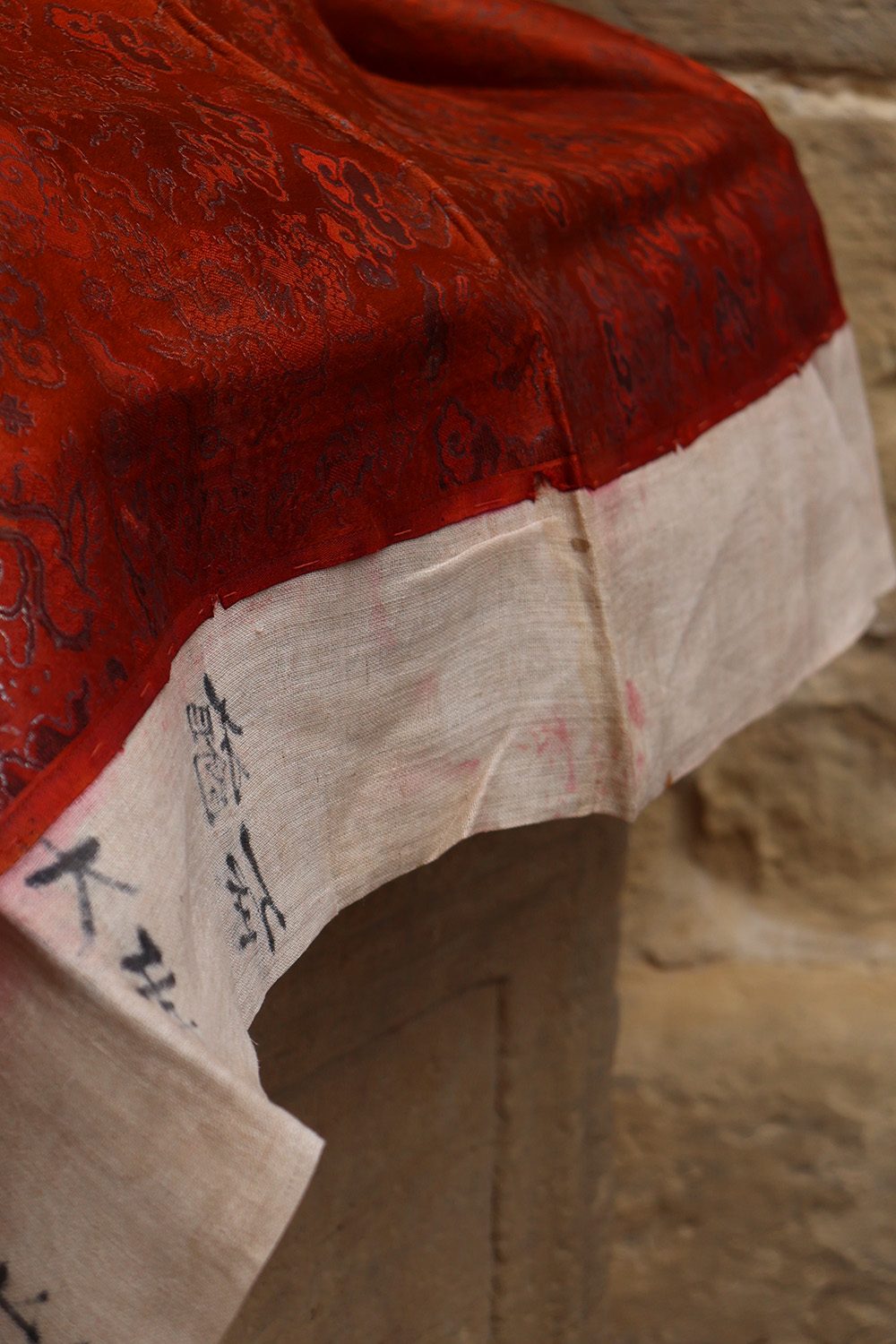

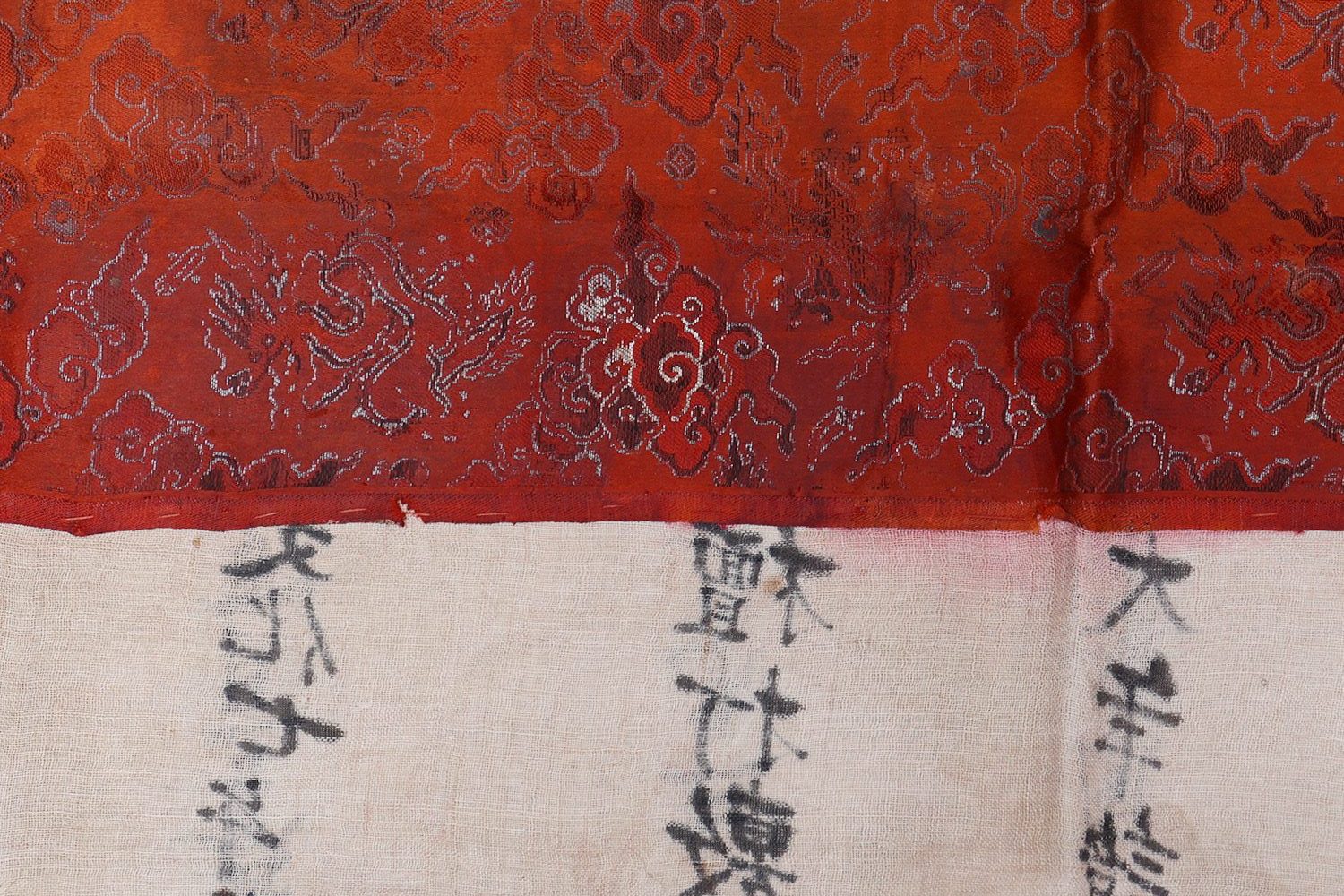

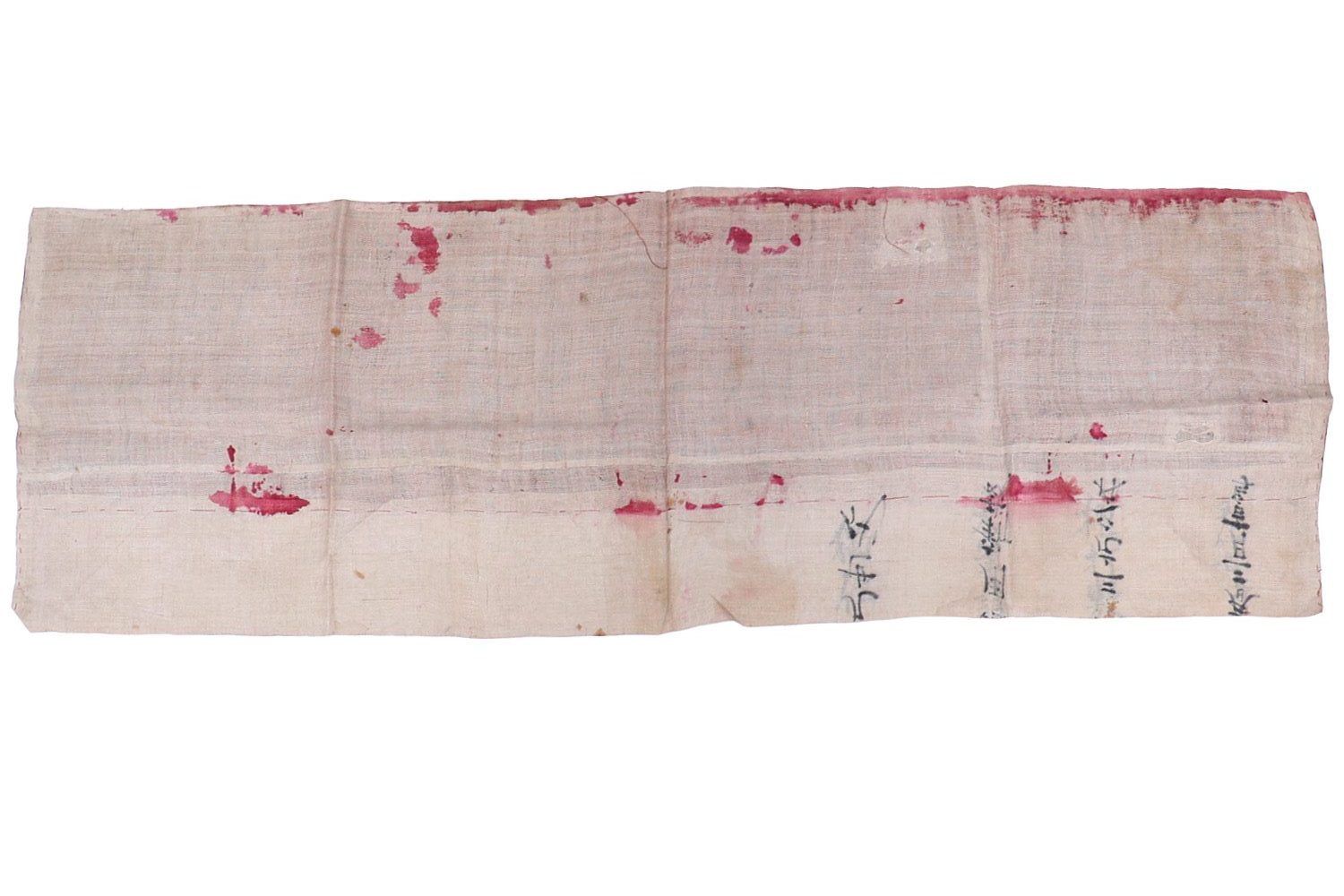

Nowadays, uchishiki tend to be kept for special ceremonies, such as commemorative services held for a deceased family member, the Obon festival in honour of the dead, equinox celebrations, or the New Year. Like priests’ mantles (kesa) and temple banners, they frequently bear dedicatory inscriptions written in ink on the lining. These inscriptions would have been made by a priest from the temple at the time of the ceremony in which they were used or just afterwards. They vary in length, being often limited simply to the name of the temple, the date of the donation, or the names of the donor or beneficiaries; they may however contain specific information about the ceremony in which the cloths were used, particularly in the case of centennial anniversaries of a school’s founder or of other major figures in a school’s history.

nishiki and kinran (often translated as brocade), in which the decorative motifs are produced by the introduction of supplementary weft threads, or patterning wefts, which lie on top of the ground weave. For many centuries, these highly valued textiles were imported from China, and it was not until the end of the 16th century that weavers from the port of Sakai (Osaka) and the Nishijin quarter of Kyôto had acquired the necessary know-how to imitate them.

At first borrowing heavily from the traditional repertoire of Chinese models – dragons, phoenixes, flowers, auspicious designs, and geometric patterns –, these Japanese textiles were later enriched by the addition of new motifs from India and Europe. The dragon and the phoenix occur with great regularity. Flowers, and to a lesser extent fruit, feature prominently in both Chinese and Japanese decorative arts.

The closure of Japan to most of the outside world during the Edo period (1603–1868) only encouraged a fascination within the country for those foreign goods which did manage to trickle in. Indo-European printed cotton chintz, Ottoman carpets and textiles, European “bizarre” silks with their distorted, fanciful flowers, as well as South-East Asian resist-dyed cloths, all provided a rich array of new and exciting designs which were combined with traditional patterns to completely revitalise the production of nishiki brocades in the 18th century. Despite their modest size, therefore, these altar cloths are a testimony to the adaptability and creativity of the Japanese weaver, and above all to his extraordinary craftsmanship.

This interesting antique Uchishiki Japanese altar cloth is woven with silk. The delicate motifs represent clouds and dragons and metal thread have been added. It contrasts with the back of thick vegetable fiber, which bears various inscriptions. The textile has flaws, but despite this, all its finesse and elegance can be appreciated.

Size: 138×47 cms

Origin: Japan

Made in: Edo period

1 in stock

| Weight | 0.4 kg |

|---|